Hip Pain in Running

Dr. Marc A. Bochner on

Dr. Marc A. Bochner on  Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 02:00PM

Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 02:00PM Although not injured as often as the knee, leg, or ankle and foot, the hip area is still commonly injured in distance runners. Both veteran an rookie runners alike often experience pain in the hip area.

It is important to understand exactly what, anatomically, the hip area is comprised of, as there are many different structures that can cause pain in the area of the hip. In fact, many runners describe pain as coming from what they think is their hip when the pain is actually coming from other areas nearby, such as the lower back and the rest of the pelvis.

The hip is a joint made by the meeting of the femur, or thigh bone, and part of the ilium, or hip bone. When taken together with the rest of the ilum, the sacrum, and the coccyx and the muscles that attach to these bones, the whole area is known as the pelvic area. The joints between the sacrum and each ilium are known as the sacroiliac joints, one on each side. The major muscles to be concerned with in the hip and pelvic are named below in discussing the specific area of injury.

Functionally, the hip, of course, is subject to impact forces as it plays its role in the running gait. The joint is involved in absorbing the impact of landing, and in the push off and extension of the leg as we propel ourselves forward. These functions cause a lot of stress to be applied to the joint, and if the body cannot handle this stress, overuse injury to the hip will occur. As in all running overuse injuries, the body’s ability to handle the stress of running will be decreased by several factors, such as running too much, too far, and too fast for your training level, not enough recovery time, worn out shoes, and poor nutrition. Also, biomechanical factors intrinsic to your body, such as overpronation, muscle strength imbalances, malignment, leg length inequality, and lack of range of motion/flexibility will decrease the body’s ability to absorb the stress of running without injury. Fortunately, the body does not break down “all at once” (although it may feel that way after a tough race or long run). First to go are usually the “soft-tissues“, meaning the muscles, fascia (which lines the muscles in certain locations), tendons (which attach muscle to bone), bursae (fluid filled sacs that provide gliding of tendon tissue over underlying bone) and ligaments (which attach bone to bone). Also, nerves can be irritated or entrapped. If attention is not paid to these soft-tissues, then the joint and bone tissues will be put at risk for injuries such as degenerative arthritis, hip impingement, labrum tears, and stress fractures, which can be harder to treat. This article will focus on the soft-tissue injuries due to space considerations.

The muscles of the hip must be strong and flexible to give the joint its proper range of motion to do its job. Problems will occur when, because of the factors discussed above, the muscles and/or fascia gradually tighten and lose their normal length. The individual muscle fibers develop adhesions between each other. This change in the muscle itself can be the injury and cause pain upon use. If not released, eventually the tendons, especially where they meet the muscle and where they attach to the bone, can also tighten, swell and weaken. They will not have the strength to do their job. Also, the bursa can get inflamed, but usually only if you totally ignore the pain for weeks or run way longer than you are used to in one run.

What is the first symptom of hip muscle, tendon, or bursa injury? Pain may start as an dull ache during a run or after, although it can be sharper in some muscles or if you have been ignoring the initial pain, and the injury is progressing past the initial stages. Most commonly involved in running are the hip abductors, the gluteus medius and minimus, and the tensor fascia latae (TFL), which is also involved in iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS). (ITBS may be felt at the hip or knee). Also commonly involved are the piriformis and small hip rotator muscles, located just below the gluteals, and the hip extensors (the gluteus maximus and hamstrings). Pain from any of these muscles can be felt at the upper buttock, outer hip, and/or down the outer or back of the thigh. The pain down the thigh is called referred pain, and can be confused with sciatic pain. Next most common are the hip flexors (psoas, sartorius, and rectus femoris), which cause pain in the front of the hip joint and down the front of the thigh and/or groin area. And finally are the adductors, which cause pain in the front and inner thigh,. If your injury is in it’s earliest stages, self-treatment may be helpful. Self-treatment of any of these muscles should start with gentle self-stretching, “rolling” the tight muscle/fascia area on a tennis ball or foam roller, applying ice to the involved areas, and possibly not running for a few days, depending on the severity of symptoms: If you are having pain during of after a run in the muscles that does not go away after two days rest and self-treatment, more rest may be needed. Non-impact cross-training such as the elliptical, cycling, or swimming may be OK. If after a week of rest, pain is still present with daily activities or returns in the same way after a run, professional treatment should be sought.

Professional treatment involves a thorough history and exam to make sure there already is not a joint or bone problem, or a complete muscle tear. The whole lower extremity, from the foot to the lower back, should be examined, and any doctor or therapist you see should be a specialist in running injuries and include a visual or videotape analysis of your walking and running form when the pain subsides enough. This analysis is essential to prevent the injury from reoccurring as it can help identify the predisposing intrinsic factors. If the injury is diagnosed as muscle or muscle and tendon, or also the bursa is involved, manual soft-tissue treatments such as A.R.T. (Active Release Technique), should be used to release the tightened muscle and fascial tissue that is causing the pain. In A.R.T., the doctor or therapist uses his or her hands to contact the tightened area, and either the doctor or patient moves the affected body part to create tension which releases the restriction in the muscle. Treatment will take more visits the longer the injury has been there, because the soft-tissues will be more damaged, or “fibrotic”. Once the muscle and fascia is released, stretches can begin to keep it released. If the area is too tight or swollen for manual treatments, physical modalites such as electric stimulation and/or ultrasound may have to be used first until the area can be treated manually.

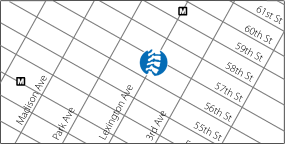

The next step in treatment is to correct the training errors and biomechanical deficits discovered throughout the body that caused the injury. The most common general pattern of muscle imbalance related to hip injury is weakness or inhibition of the hip abductors and hip extensors, and tightness of the hip adductors and hip flexors. Other muscle imbalances, such as a weak core, should be addressed as well. Generally, to isolate the weak/inhibited muscles, floor exercises and non-weight bearing exercises involving bands, ankle weights, or machines are first used, progressing to standing exercises with multiple joint motion, such as squats and lunges. Balance exercises on unstable surfaces such as the wobble board, stability ball, and half foam roller are then added, and finally impact activities like plyometric drills (bounding, hopping, and box jumps) are sometimes done. Functional and anatomical leg-length inequality can be corrected by spinal adjustments and heel lifts, respectively. Overpronation secondary to muscle imbalance is corrected with stretching and strengthening, usually of the deep calf muscles, and primary overpronation is corrected with orthotics. Running, starting with even just 10 minutes, then can begin, preferably on soft surfaces such as the reservoir. Resuming running before completing a rehabilitation program invites risk of re-injury, even if you can run pain-free after the soft-tissue treatments! Finally, to keep the injury from reoccurring, as well as to keep your body at it’s highest level of preparedness for running, and maintain longevity in the sport of running, a maintenance, or “prehabilitative” program of self-care is essential! To keep the muscles and other soft-tissues strong and pliable enough to absorb the impact of running, one can continue some of the key rehab exercises, plus use tennis ball/foam-rolling, active stretching pre and post runs, yoga, and strength training including core and upper body postural exercises. Also, it is wise to pay attention to your running form/technique and have a proper training plan for your ability level.